RIVERSIDE, Calif. – Chemists at the University of California, Riverside have accomplished in the lab what until now was considered impossible: transform a family of compounds which are acids into bases.

As our chemistry lab sessions have taught us, acids are substances that taste sour and react with metals and bases (bases are the chemical opposite of acids). For example, compounds of the element boron are acidic while nitrogen and phosphorus compounds are basic.

The research, reported in the July 29 issue of Science, makes possible a vast array of chemical reactions – such as those used in the pharmaceutical and biotechnology industries, manufacturing new materials, and research academic institutions.

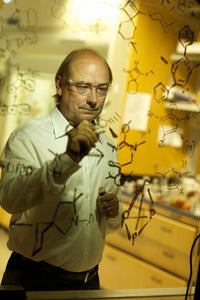

“The result is totally counterintuitive,” said Guy Bertrand, a distinguished professor of chemistry, who led the research. “When I presented preliminary results from this research at a conference recently, the audience was incredulous, saying this was simply unachievable. But we have achieved it. We have transformed boron compounds into nitrogen-like compounds. In other words, we have made acids behave like bases.”

Bertrand’s lab at UC Riverside specializes on catalysts. A catalyst is a substance – usually a metal to which ions or compounds are bound – that facilitates or allows a chemical reaction, but is neither consumed nor altered by the reaction itself. Crucial to the reaction’s success, a catalyst is like the car engine enabling an uphill drive. While only about 30 metals are used to form catalysts, the binding ions or molecules, called ligands, can number in the millions, allowing for numerous catalysts. Currently, the majority of these ligands are nitrogen- or phosphorus-based.

“The trouble with using phosphorus-based catalysts is that phosphorus is toxic and it can contaminate the end products,” Bertrand said. “Our work shows that it is now possible to replace phosphorus ligands in catalysts with boron ligands. And boron is not toxic. Catalysis research has advanced in small, incremental steps since the first catalytic reaction took place in 1902 in France. Our work is a quantum leap in catalysis research because a vast family of new catalysts can now be added to the mix. What kind of reactions these new boron-based catalysts are capable of facilitating is as yet unknown. What is known, though, is that they are potentially numerous.”

Bertrand explained that acids cannot be used as ligands to form a catalyst. Instead, bases must be used. While all boron compounds are acids, his lab has succeeded in making these compounds behave like bases. His lab achieved the result by modifying the number of electrons in boron, with no change to the atom’s nucleus.

“It’s almost like changing one atom into another atom,” Bertrand said.

His research group stumbled upon the idea during one of its regular brainstorming meetings.

“I encourage my students and postdoctoral researchers to think outside the box and not be inhibited or intimidated about sharing ideas with the group,” he said. “The smaller these brainstorming groups are, the freer the participants feel about bringing new and unconventional ideas to the table, I have found. About 90 percent of the time, the ideas are ultimately not useful. But then, about 10 percent of the time we have something to work with.”

The research was supported by grants to Bertrand from the National Science Foundation and the U.S. Department of Energy.

An internationally renowned scientist, Bertrand came to UCR in 2001 from France’s national research agency, the Centre National de la Recherche Scientifique (CNRS). He is the director of the UCR-CNRS Joint Research Chemistry Laboratory.

A recipient of numerous awards and honors, most recently he won the 2009-2010 Sir Ronald Nyholm Prize for his seminal research on the chemistry of phosphorus-phosphorus bonds and the chemistry of stable carbenes and their complexes.

He is a recipient of the Japanese Society for Promotion of Science Award, the Humboldt Award, the International Council on Main Group Chemistry Award, and the Grand Prix Le Bel of the French Chemical Society. He is a fellow of the American Association for the Advancement of Sciences, and a member of the French Academy of Sciences, the European Academy of Sciences, Academia Europea, and Academies des Technologies.

He has authored more than 300 scholarly papers and holds 35 patents.

Bertrand was joined in the research by Rei Kinjo and Bruno Donnadieu of UCR; and Mehmet Ali Celik and Gernot Frenking of Philipps-Universitat Marburg, Germany.

UCR’s Office of Technology Commercialization has filed a provisional patent application on the boron-based ligands developed in Bertrand’s lab.